Category:Psychedelics

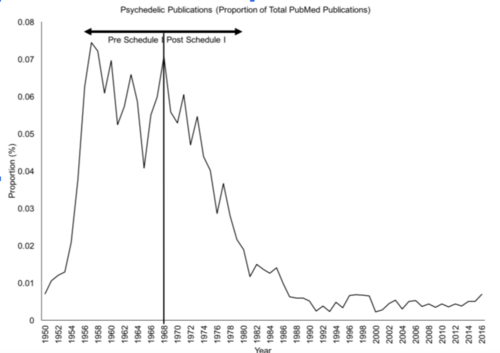

There are one of three categories of hallucinogens, with the others being dissociatives and deliriants.[53] Psychedelics are generally considered physiologically safer than most other groups and as of recently are experiencing decriminalization or even legalization in some areas. [3] There has also been a “Psychedelic Renaissance” with an increase in scientific research that was stalled during the 1970s that is finding that psychedelics may have a strong potential to be useful in treating a variety of psychological disorders.

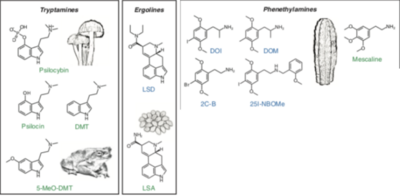

Generally, psychedelics are defined as serotonergic hallucinogens (specifically the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor) that alter perception and mood in a marked novel way along while affecting numerous cognitive processes.[3][50] More concretely the “classical psychedelics” all share agonist actions at the serotonin 2A receptor subtype (5-HT2A). [1] This class contains a wide variety of compounds and has some well known drugs such as LSD, psilocybin mushrooms and DMT, with LSD being the archetypal psychedelic in modern Western society.[4] This is due to LSD having the “highest and most specific effect” while also being the basis of the contemporary concept of psychedelics and the far-out social movement.[2] Many psychedelics can be found naturally in fungi, plants, and even some animals.[82] Although, some of the compounds have a long history of human usage and some of the most in-depth scientific research, others have been synthesized rather recently and have little to no human usage. This section will specifically focus on psychedelics and will consider cannabinoids, dissociatives, entactogens, and deliriants in separate sections.

The term ‘psychedelic' itself has an interesting history. It was coined by psychiatrist Humphrey Osmond in a letter he wrote to Aldous Huxley and presented to the New York Academy of Sciences in 1965 .[4][43][46][107[ This was in regards to the insightful effects that often occurred from psychedelics during treatment for addiction.[64] The word ‘psychedelic’ is a neologism derived from the ancient Greek words psych"e (jycή, translated as “soul” or “mind”) and d"elein (dhlεin, translated as “to reveal or “to manifest”) to denote ‘mind-revealing’.[2][4][46][50][121] Prior to Osmond there were a variety of terms used to describe these substances such as: psychotomimetics (implying psychosis), psychotogens, psychodysleptics, deliriants, hallucinogens and mind-expanding drugs, however many of these carry negative connotations.[27][3] For example, Psychotomimetics, a negative term suggesting that they fostered a mental state resembling psychosis, used to be the preferred term in scientific literature. Lat[3]er, when it was realized that these substances did not provide a model for psychosis, it became correct to refer to them as hallucinogens suggesting that they principally produce hallucinations.[3] However, this is not particularly descriptive or useful since hallucinations are not always produced, along with it describing a too broad category of psychoactive molecules.[3] In a recent paper David E. Nichols described the history:

History

Psychedelics have a long and controversial history. They have had a profound impact on every culture that has interacted with them. Due to the altered state they produce plant-based psychedelics (along with fungi-based psychedelics and occasionally even animal-based) have been used by humans for spiritual and religious purposes for centuries, if not millennia.[1][27][3][50][55][64] There is extensive evidence that various psychedelics were used by early cultures in sociocultural and ritualistic purposes.[44][64] The earliest direct evidence for use of psychotropic plants dates back 5700 years ago in the north eastern region of modern day Mexico, however there are murals and other evidence that suggests that it may be longer.[4] Some important examples of substances used by early cultures include a substance used in ancient India known as Soma.[3] This was a drink (with the exact psychoactive compound still debated) that was highly revered in Vedic tradition.[3] Psilocybin mushrooms have been used by Aztec Shamans in a variety of religious and divinatory rituals along in many other mesoamerican cultures.[3] Peyote (mescaline) is a small cactus native to southern North America that has been used by native americans for at least 6000 years.[3] Ayahuasca (DMT) is a decoction that has a long history of use by natives in the Amazon valley of South America.[3] There are even many more substances and cultures over the course of history. The counterculture of the 1960/70s is the most commonly known ‘culture’ that is associated with psychedelics.

Although people have been using these substances for millenia, the modern scientific history of these compounds began with the first medical reported use of a classical psychedelic in Western medicine in 1895.[4] Prentiss and Morgan first reported the ceremonial use of buttons of the peyote cactus (mescaline) by indigenous people in Central America.[4] During self-experimentation Prentiss and Morgan reported closed-eye visuals as an “orgy of vision”.[4] Unlike many other drugs discovered over the past 100 years, the effects of psychedelics were first characterized in humans before animals.[1] This was followed by the isolation of mescaline by Heffter in 1897, although there is limited further mention of mescaline in literature until 1913 and little to no use by psychiatrists due to mescaline never being marketed.[1][4] About 30 years later Albert Hofmann synthesized LSD in 1938 as part of a systematic investigation of compounds derived from the ergot alkaloids where he discovered LSD’s psychoactive effects in 1945.[1][4] In contrast to mescaline, LSD was marketed and provided to psychiatrists free of charge.[4]

Psilocybin mushrooms would also play a significant role in the early history of psychedelics in western science and culture. R. Gordon Wasson and his wife Valentine P. Wilson traveled to the town of Huautla de Jiménez in Oaxaca, Mexico, in June and July 1955 with photographer Allan Richardson.[6][52] Here they met with the Oaxacan shaman Maria Sabina to participate in a mushroom ritual.[51][52] Maria gave Wasson about thirteen pairs of fresh Psilocybe caerulescens to ingest.[51] This trip was chronicled in a May 13, 1957 photo-essay in Life Magazine. “Seeking the Magic Mushroom”.[51][52] It introduced psychedelic mushrooms to an entire generation of Americans in the pre-sixties social period where LSD had not yet gained national notoriety.[51] This article would lead Timothy Leary, one of the most influential psychedelic advocates and researchers, to Mexico where he consumed psilocybin mushrooms for the first time. He is famously quoted as saying he:

The discovery of LSD in 1943 “turned the key in the ignition of the psychedelic era”.[2] However, the true beginning was 1953. In this one pivotal year, R. Gordon Wasson and his wife confirmed the existence of a surviving “magic mushroom cult” in Mexico.[2] William Burroughs drank the hallucinogenic yagé brew in the Upper Amazon and wrote to Allen Ginsberg, who rushed down to try it.[2] Aldous Huxley was introduced to mescaline by Dr. Humphrey Osmond, who was preparing to test the psychoactive properties of the morning-glory seed.[2] American Military intelligence was performing clandestine research (project Bluebird/Artichoke) on psychedelics as possible agents in psychological and chemical warfare.[2] It was also about the time that psychiatric researchers, many of whom had by then taken LSD and mescaline themselves, instead of simply administering the drugs to their patients, began moving away from psychotomimetic theory.[2]

Due to the profound effects of psychedelic drugs on behavior, specifically the unique potency and effects of LSD, a significant wave of studies into the potential medicinal uses of these drugs began in the late 1950s and lasted throughout the next decade.[1][4][3][50] There were three general psychedelic agents at the time: mescaline sulfate, psilocybin, and LSD-25.[89] There was an extensive amount of research being done with these substances due to specialists noting their ability to possibly shorten psychotherapy because of factors such as: acute intoxication having similar symptoms of acute psychosis (ego-dissolution + visual perception) and an increased awareness of the subconsciousness.[4][50] There was also increasing experimentation with non-mentally ill patients, demonstrating the remarkable therapeutic potential of psychedelics.[2] This new wave of studies even caught mainstream media’s eye; There were reports on LSD and its growing use in psychiatry, along with undergraduates taking LSD as part of their education.[96] The published literature on the potential medical value of psychedelics grew enormously.[121] According to Dyck, “LSD trials represented a fruitful, and indeed encouraging, branch of psychiatric research occurring alongside more famous and successful trials of the first generation of psychopharmacological agents…”. Between 1950 and the mid-1960s there were more than a thousand papers discussing 40,000 patients, along with dozens of books and international conferences.[3][50][55][64] One of the main things being studied with LSD was the “psychomimetic” (i.e. psychosis mimicking) effect.[4][89][96] Scientists at the time were looking for way to cure the “disordered mind”.[89] It was thought that if schizophrenia and psychosis could be duplicated for a period, then science may be on the way to finding a cure.[89] Although this theory has flaws it did lead to many interesting studies into psychedelics and the mind.[89] There were many important researchers and studies done in this time period. Many may not have been up to the standards we have today, but they set a good base of knowledge along with getting many psychedelic advocates involved. People like Ken Kesey, Bill Wilson, and Timothy Leary got involved through either running or participating in different types of studies.

In 1960 Dr. Sidney Cohen, a leading expert on LSD and other mood altering drugs at the time, wrote to 62 doctors who had published papers on their use of psychedelics.[89] In the survey, not a single physical complication was reported.[89] There was also a surprisingly low incidence of major mental disturbances, even when in some cases negative reactions were deliberately brought about (trying to produce “model psychoses”)[89] Although the design of these studies was suboptimal, a recent meta-analysis of studies done during this period found that 70% of patients showed ‘clinically judged improvement’ post treatment.[4][50] The research conducted prior to 1970 suggests while there was interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelics, a firm conclusion about efficacy and safety was not reached prior to illegalization.[4][64] The subsequent psychedelic research ultimately lead to the whole field of serotonin neuroscience along with the hypothesis that the action of LSD was due to the interaction with serotonin systems.[3] By the 1960s the U.S. Army and CIA also realized the potential LSD possessed and had conducted their own numerous experiments and stored considerable stockpiles.[89] The CIA had created a research program code-named MK-ULTRA that conducted secret research investigating LSD for application in ‘mind control’ and chemical warfare from 1953 and until the program halted in 1973.[89][94]

The counterculture during the the 60s (especially the hippie movement) brought psychedelics into greater popularity when people began using them for recreational and spiritual purposes.[105]. This was in stark contrast to the “conformist, gray-flannel Fifties”.[2] This ‘era’ would be described as the “psychedelic era” due to social, musical, and artistic changes being influenced by psychedelic drugs.[77] Throughout the 1950s, mainstream media covered research into LSD along with describing its effects.[77] Popular interest grew with LSD-user Cary Grant’s interview in Look. Even TIME magazine published six positive reports about LSD between 54’ and 59’.[77] Although there is no specific origin to the “psychedelic era”, in the late 1950s Beat Generation writers, such as Ginsberg and Burroughs, wrote about and took drugs raising awareness and helping to popularize their use.[77] Aldous Huxley published The Doors of Perception, nearly losing his reputation but reaching a wide audience of intellectuals with his positive account of mesacline’s power.[2] The psychedelic lifestyle had already developed in California, particularly in San Francisco, by the mid 1960s.[77][78] However, few could begin to predict the shattering impact psychedelics would have upon the electrical generation of rock-and-roll rebels of the sixties.[2] By 1962 Michael Hollingshead, a British researcher, “turned on” Timothy Leary, Alan Watts and other early psychedelic activists who would go on to change on how LSD was viewed.[89][91]

LSD first began being used recreationally in certain, mainly medical, circles.[96] Academics and medical professionals, who became acquainted with LSD through their work, began using themselves and with associates.[96] Several prominent intellectuals such as Timothy Leary, Al Hubbard, and Alan Watts began to advocate for the mass consumption of LSD.[90] This led to LSD becoming a central, highly-visible feature of the youth-driven counterculture of the 1960s.[90] Across the U.S. many people developed a desire for a “psychedelic” trip, in contrast to a “psychotomimetic” one (which appealed to few).[89] Without access to certified dispensing physicians, many soon determined they would be getting some anyway.[89] However, few could begin to predict the shattering impact psychedelics would have upon the electrical generation of rock-and-roll rebels of the sixties.[2]

The counterculture and hippie movements during the 1960s and 70s were an evolution of the beat generation of the 50s.[132]

- The outspoken Harvard professor Timothy Leary[3]

- “Turn on, tune in, and drop out” → take drugs to discover your true selves and abandoned convention[3]

- Current Day historians suggest that the termination and promotion of psychedelics by Timothy Leary “further undermined an objective scientific approach to studying these compounds"

LSD was more important than Harvard

- Terrence Mckenna

- Owsley Stanley

- sound engineer for the Grateful Dead[78]

- “Owsley Acid” became the new standard after Sandoz stopped producing LSD[78]

- Primary LSD supplier for Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters[78]

- Grateful Dead

- Hippie movement

- Merry Pranksters

- Electric Kool-aid acid test/acid tests

- Ken Kesey

- ‘Further’

- Summer of Love

- Haight-Ashbury

- Peace/Love

- Merry Pranksters

- It is believed that more than 30 million people have used LSD, psilocybin, or mescaline[3]

- In his 1979 book LSD — mein Sorgenkind ("LSD — my problem child"), Hofmann described the problematic use of these hallucinogens as inebriants.[6]

- One suspects that had LSD not been discovered the world would be a very different place then it is today, for better or for worse

- “The newspapers in these cities [San Francisco, New York, Chicago] have been fascinated by the psychedelic hippies, and at times the fascination has verged on obsession. In New York, the Times has devoted many columns of newsprint to their doings, and in San Francisco, the Chronicle sent a bearded reporter out to spend a month prowling the acid dens. (You guessed it: ‘I was a Hippie.’)” - William Braden in “LSD and the Press,” (1970)[2]

Chemistry + Chemical Classes

There are the better known ‘classical psychedelics’, such as psilocybin mushrooms and LSD but there has also been an increase in psychedelic research compounds. The classical psychedelics will be separated out because although they vary in structure, their influence on culture and science is significant. Research chemicals are structurally similar to the classical psychedelics however with slightly different chemical structures and effects.

This grouping of subclasses will be used in this paper with the addition of the ‘classical psychedelics’ and ‘entheogens’. Entheogens are psychedelic substances that have been particularly used in traditional or herbal forms, but may still have recreational use.[44] This specific term was coined to avoid the negative connotations of the words hallucinogen and psychedelic and can be translated to mean ‘God generating’.[43] These tables are the current list of substances that I could find, however new ones are added frequently. For example just as recently as 2022 a new lysergamide, 1D-LSD, was synthesized. This was the result of 1V-LSD being outlawed in Germany under their NpSG law.[69] There may also be some overlap between grouping as well.

Lysergamides

Further information--> Lysergamides

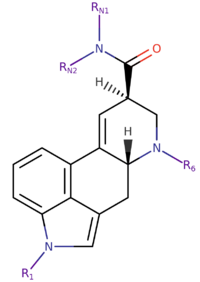

Lysergamides, often known as ergoamides and lysergic acid amides, are amides of lysergic acid with many having potent agonist and/or antagonist activity at various serotonin and dopamine receptors.[46] The base psychoactive lysergamide is LSD[44]. Lysergamides are polycyclic amides which have both phenethylamine and tryptamine groups embedded within their structure and a carboxamide group attached to carbon number eight[65][80] The combination of tryptamine and phenethylamine often results in the subjetive effects being described as a combination[46][80]. Varying the substituent attached to the nitrogen atoms has produced a variety of drugs with psychedelic effects[65]

The simplest lysergamides are ergine (lysergic acid amine, LSA) and isoergine (iso-lysergic acid amide; iso-LSA).[66] In terms of pharmacology, the lysergamides are similar to other serotonergic psychedelics but also interact with numerous dopamine receptors.[65][66]

| 1B-LSD | 1cP-LSD | 1P-LSD | AL-LAD | LAE-32 | LSM-775 | LSZ |

| EcPLA | ETH-LAD | LSA | 1cP-AL-LAD | LSH | MiPLA | PARGY-LAD |

| 1cP-MiPLA | 1V-LSD | ALD-52 | EiPLA | LSD | PRO-LAD | 1cP-ETH-LAD |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Carhart-Harris, Robin L. (2019). "How do psychedelics work?" Current Opinion in Psychiatry 32(1): 16–21.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 Aldrich, M. R.; Ashley, R.; Horowitz, M. (1978). High Times Encyclopedia of Recreational Drugs. Stonehill.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 3.17 3.18 Nichols, David E. (2016). "Psychedelics." Pharmacological Reviews 68(2): 264–355.|doi=10.1124/pr.115.011478

Pages in category "Psychedelics"

The following 5 pages are in this category, out of 5 total.